On João Gilberto

by Fred Thomas

“The only thing better than music is silence, the only thing better than silence is João” – Caetano Veloso

One glorious day, in a random flat in Barcelona, I first heard João Gilberto’s solo album “João Voz e Violão”. The impression those uncannily intimate sounds made on my adolescent brain has shaped my musical life. I was transfixed by tenderness. Soon I was listening to his records compulsively, picking out the harmonies and rhythms and trying to figure out by which trick of magic the vocals related to them. Aged 16, I instinctively knew I was hearing something very special and strange. Almost 20 years later, the same mysterious obsession still follows me around and has led me to attempt to play his songs, emulate his musical values and write this text.

It’s written for music lovers of all kinds, and non-musicians won’t miss much by skipping the few bits that are technical. But it’s also for those who associate João with the kitsch new wave of the 1960s, with hedonistic Stan Getz saxophone solos, with cringey lyrics in English, with saccharine pseudo-jazz, with light breeziness (and all the other vague terms used by journalists to try and capture him). I will present an altogether different persona and demonstrate that the mature João I love, who played only solo concerts, could not be further from his superficial caricature. He was, in fact, a countercultural aesthetic monk.

My proposition is that what João didn’t do is at least as important, if not more important, than what he did do. His artistry is best understood in terms of the strict limits he imposed on himself and the soaring freedom he attained within them. João is the ultimate archetype of this time-honoured paradox. His musical process involved a search for what he called “the simple truth”. With his recordings and live concerts as our deep listening guide, we will try to find out what his truth means.

With a tenacity bordering on obsessive-compulsive, João delineated his stylistic perimeters, rejecting many of the characteristics most commonplace in music for voice and guitar. Through sheer stubbornness, he managed to set up an enclosed and rule-based system that nevertheless cultivates a specific kind of infinite freedom of phrasing. Beneath their surface layer of simplicity, his recordings are intricate, elusive and, above all, subtle. In other words, João unearthed the holy grail of music making: the transformation of extreme complexity into sounds that are simple, relaxed and clear. Sounds that just float into our minds.

João’s musical style balances exquisitely at the edge of a precipice: just a hint of lush orchestration plunges it into an abyss of queijo. On richly orchestrated and over-produced albums such as “João” and “Amoroso”, arrangers lead us by their grubby hands straight into the elevator: a sublime Japanese ink-drawing transformed into a sicky oil painting hung on a hotel room wall. To those who associate João with easy listening, I simply say, “your listening is too easy, try harder”. His musical essence is minimalist, single-minded, rigorous, unsentimental and child-like: “maybe I would like to go back to when I was a boy,” he said. “After that I learned too many things, and they came out in my music. So now I refine and refine until I can get back to the simple truth. Like when I was a boy”.

Instrumentation and Repertoire

Within João’s earliest work there are many exceptions to the claims set out below. But I’m going to be dealing with his mature solo albums: “JoãoVoz e Violão”, “In Tokyo”, “Live in Montreux”, “Live at Umbria Jazz” and “Eu Sei Que Vou Te Amar”. To my taste, as soon as other instruments were added to his voice and guitar, the music very quickly got worse. My one exception to this rule are Sonny Carr’s narcotic hi-hats on the 1973 album “João Gilberto”, often referred to as the white album (which I will therefore add to my list). By purging everything from his percussion set except these essential hi-hats, Carr mirrors João’s stripped back musical proposition, blending perfectly with the guitar meanwhile. Whether it was Carr, producer Rachel Elkind or João himself who took this radical instrumental decision, it was a masterstroke that lends this hugely influential album its uniquely soporific atmosphere.

Apart from the odd song in Spanish (“Besame Mucho”), Italian (“Estate”), English (“’S Wonderful”), French (“Que Reste-T-Il De Nos Amours”) and the few pieces he composed himself such as “Bim Bom” and “Hô-bá-lá-lá“, João’s huge repertoire derived from three essential Brazilian sources. Having started his career as a drummer in Bahia, João broke through showcasing the radical songs of Tom Jobim/Vinicius de Moraes and other late ‘50s composers, before going on to combine these Bossa Novas with older tunes by composers such as Ary Barroso, Denis Brean and Dorival Caymmi, excavated from the forgotten past. To complete the triangle, the Tropicália movement from the late ‘60s and ‘70s – founded by young apostles such as Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil – provided João with the likes of “Coracão Vagabundo”, “Menino do Rio” and “Sampa”. To this extent, João encompasses the past, present and future. Yet it is remarkable that, filtered through his ultra-fine stylistic sieve, every song he interpreted sounded fundamentally the same. And I mean that as a great compliment. In precisely that way, João is a true minimalist.

Until his last performance in 2008, João continued to play the same hit songs. This insistence was not only generosity to his audience, always gagging for yet another version of “Desafinado”. It also speaks to the sense that, as in jazz, the process was more important and more interesting than the content. During the performance of a song, João would often repeat it over and over, more times than the average listener with limited concentration considered reasonable. Yet each round was phrased uniquely. His search for perfection was obsessive, devotional even; he could repeat forever without repeating himself. “Fazendo sempre a mesma coisa que nunca é a mesma” – always doing the same thing that’s never the same, said Caetano Veloso.“Refine and refine”, even within a six-minute song.

Embedded in João’s performance process was an infinite search for the perfect rendition. Only microscopic listening exposes this. For those who hate “Garota de Ipanema”, try this version and witness the total transformation of a dodgy song of youth, hacked to death at weddings and functions for sixty years. In João’s hands, it touches the sublime. His “refinement” acts at both micro and macro levels: within a song and over a lifetime. Supremely focused yet never satisfied, João’s single-mindedness reminds me of Thelonious Monk, another obsessive who likewise poured over the same repertoire until his last breath.

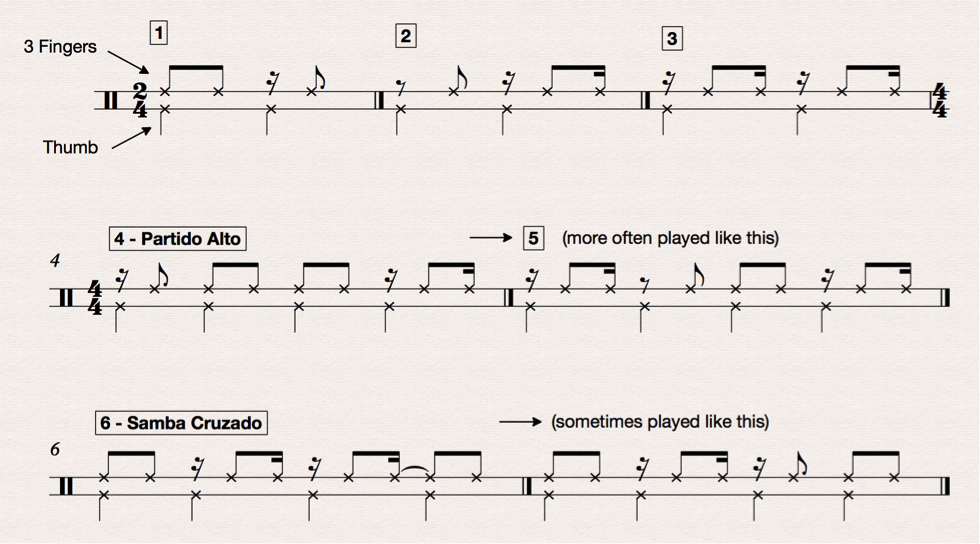

Rhythm of the Guitar

Apart from the odd waltz, all of João’s music is in 2/4 or 4/4. His right hand is divided into two parts: thumb and three fingers (his little finger does nothing, in line with traditional classical guitar technique). The thumb plays a bass note on every beat (crotchet), always. He never precedes that note with a repeated upbeat, as a kit drummer playing a Samba would articulate on the bass drum. Nor does he ever change the bass note without changing the chord above it: his bass-lines don’t go “I – V, tonic – dominant”, as is often assumed. There is a clear trajectory from the surdo in a Samba bateria to João’s thumb. It’s the one thing in the music that never changes, a kind of single-stroke heartbeat, omnipresent and absolutely regular. Oh thumb, how comforting you are…

The three fingers above it (in pitch) deliver a distillation or abstraction of rhythmic phrase called Partido Alto. This is a foundational pattern derived from Samba’s rhythmic superstructure, represented by the tamborim (sometimes called ‘teleco-teco’) in a bateria (see Figure 2). In a slightly different form, the tamborim’s rhythm can also be heard in an even older musical style, Candomblé de Angola. The Partido Alto can be described as a clave (see Francesc Marco’s detailed definition of clave here). The concept of clave is a profound way of organising rhythm (equivalent to harmony), expressed as a looping phrase that defines the rhythmic identity and serves as a reference point for the other participants. Partido Alto is the rhythmic reference in Samba. Those familiar with that music perceive two halves of the phrase: syncopated (beats 1 + 4) and unsyncopated (beats 2 + 3). When other rhythms (in João’s case melodies) are set against the Partido Alto, they feel different depending on which “side” of the clave they fall.

João’s fundamental grooves can be summarised as follows:

Figure 1.

Here are some examples:

1. “Estate” from “Live in Montreux“

2. “Menino do Rio” from “Live in Montreux“

3. “Curare” from “João Gilberto Prado Pereira de Oliveira – Ao Vivo“

4. “Desafinado” from “João Gilberto Prado Pereira de Oliveira – Ao Vivo“

5. “Sem Compromisso” from “Live in Montreux“

6. “Pra Que Discutir Con Madame” from “Live in Montreux“

N.B. If you write every pattern in 2/4 then there is no need to explain Samba Cruzado: it’s just Partido Alto sat in a different position to the harmony (on the other side of the bar). Although the phenomenon of Cruzado rarely exists in more traditional Samba, it’s a style referred to by Bossa Nova musicians, who composed without the rhythmic strictness of Samba. Their sense of the relationship between rhythmic tension and harmonic tension was a little looser than in Samba, where the hook-ups are very precise, particularly when ending phrases and approaching beat 1. Most Brazilian music, for example Chorinho, was traditionally written in 2/4. But in music derived from Samba the rhythmic cycle lasts for 4 beats, so this question of Cruzado arises. Another good example is the song “Samba De Uma Nota Só“, which demonstrates that wherever the melody sits, the accompaniment should follow. There is a big debate around how to define this phenomenon, which appears in other Latin American music that uses clave. But it’s only when bar-lines are imposed on an orally transmitted music that the problem arises.

Figure 2.

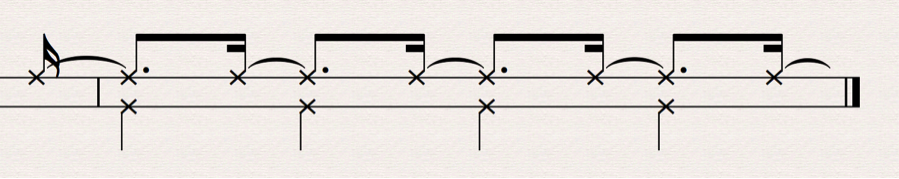

In fact, João’s three fingers offer an ever-changing constellation of rhythmic patterns, flowing seamlessly into one another within a song. Defining exactly how and why he constantly interchanges them is hard. Cultivated over so many years, this elastic flow of rhythmic ideas is perhaps simply an instinctive response to melody and text. João has countless combinations and variations at his disposal. For example, when he needs to change chord on every beat, he often does this:

João’s upper three fingers almost always play block chords, all the notes plucked simultaneously. At slow tempos (speeds), he occasionally plays a sequence of chords as straight crotchets (e.g. “Retrato em Branco e Preto” from “Live in Montreux”) or breaks them up into quaver triplets. But putting to one side this intricate system of accompanimental variations (illustrated perfectly by “Doralice”), the basic rules are very clear: block chords plus a bass-line on the beat. Essentially, everything this video is NOT.

João’s groove is always amazing, the pulse very steady and the feeling extremely relaxed (relaxed in the specific sense of rhythmic placement). A tap along to any record will reveal just how stable he is – only occasionally on fast tunes does he get excited and speed up. It’s easy to get totally flummoxed by João’s voice phrasing wildly all over the place. I lose my balance if I concentrate only the melody. And this is precisely the key thing: dividing his brain in two, João does two seemingly incompatible things, simultaneously. His uncanny ability to conjure a perfect groove whilst soaring above with diabolical freedom is second to none. Who knows how many hours he practiced at this, but it’s surely founded on a supreme and instinctual gift.

There are a couple of exceptions to the rhythmic patterns outlined above, but they are usually one-offs such as “Undiú” or “Na Baixa do Sapateiro”. It’s worth noting that João never mutes his guitar with his right hand to make it more rhythmic or funky. Especially at slower tempos, his guitar notes are usually long and sustained. The sound is clean and you never hear the metallic sounds of the frets. He never uses his guitar to comment melodically (let alone take a solo), nor does he ever strum it.

As heard on “Aguas de Março”, João was keen on starting songs by repeating the opening chord as even quavers, before sliding into whichever rhythmic pattern the tune called for. This is a kind of extended announcement or chamada – a “waiting for the singer to come in” trick – which may derive from one of the ways the tamborims enter the music in a Samba bateria with those same “holding” repeated quavers. João sometimes even inserts them in the middle of a song, like in this beautiful version of “Aquarela do Brasil”. Witness the almost unbearable tension João generates by uncoiling and stretching out the most chromatic notes of Ary Barroso’s melody, above the unusually static harmony of F sharp diminished (from minute 1’59).

Harmony

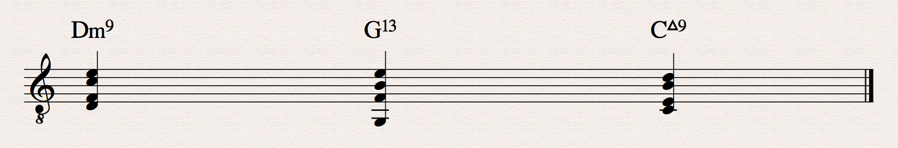

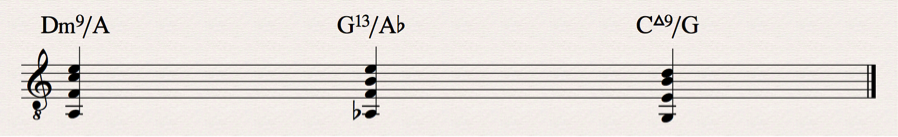

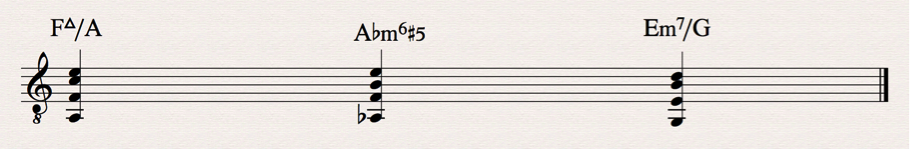

Another self-imposed limitation is this: despite playing on a six-string classical guitar, João plays only four-note chords. The rare exceptions are final chords of songs, for example “Eclipse”. The voice-leading – how the chords flow into one another – in his sequences is often (but not always) smooth. João’s harmonic language remains consistent irrespective of the repertoire. His four-part harmony is essentially founded on the functional language of jazz standards, which in turn derives from Broadway songs. This language is always logical and describable: this is what I mean by ‘functional’. There’s no João chord that cannot be adequately expressed as a chord symbol (e.g. Cm9). The fundamental difference between João’s harmonic world and that of a jazz standard is a question of inversions. An inversion is a chord placed out of its fundamental ‘root’ position, with an outer note flipped up or down an octave. A hallmark of his style, João inverts many chords, transferring them from their root positions and thus allowing his bass-lines to move in a more step-wise manner. So instead of playing:

He’ll play:

Notice how in the second example our ear accepts that the root notes (D, G, C) are missing and only implied. The function of the chords is still correct, and the voice-leading is very strong. Of course there are other ways to express these chord symbols, such as:

But that’s a whole other can of worms. Apart from a tiny handful of exceptions over his whole career, João never played a perfect major or minor triad (a three-note chord). His triads were always coloured by a 6thor 7th. Nor did he ever play a triad with an added 2nd. That’s some will power….try telling a jazz musician to never ever play an added 2nd.

Singing and Phrasing

João’s singing style is again defined by the things he refused to do. For instance, by the age of 28, the vibrato (the rapid oscillation of pitch) he had adopted as a very young singer was gone. With very few exceptions, he used no ornamentation (the decoration of melodies), portamento (slides between notes) or melismata (singing more than one note per syllable). He effected no big changes in volume or swells; his voice was always soft and in perfect proportion to his acoustic guitar. The colour of his voice didn’t change according to register, and he didn’t attempt a big vocal range. All of this is surprising, because these things tend to be the daily bread of good singing. The rhythm and inflection of Brazilian speech are of course reflected in the melodies of Samba and Bossa Nova. As he grew older, João’s singing style became more spoken. The delivery in “Segredo” is almost a spoken whisper. João’s spoken and singing voice are one and the same. When you’re pitching speech, there’s no need for a great technical leap. João is the unlikely member of a tiny clique of special humans, few and far between in the history of recorded music. Like Louis Armstrong, Ella Fitzgerald and very few others, he sounds good scatting. Whether he’s imitating the shimmering sound of hi-hats, intoning the climax of a song or casually mumbling a half-scatted intro, João always seems to be just having a chat.

The melodic phrasing of João Gilberto is a universe unto itself. He combines singing in the pocket (the rhythmic sweet spot) with floating freely over his guitar, out of time. Rubato is commonly understood as the flexible giving and taking of tempo, and this refers to the entire music – the melody and accompaniment – which moves freely but in synchrony, together as one. However, this meaning of Rubato arose as late as the 19th Century. An older 17th, 18th and early 19th Century phenomenon called Tempo Rubato was described by both Mozart and Chopin as a free melody that floats above a steady accompaniment. In other words, out of sync. Much harder to execute, this earlier form of Rubato is central to João’s musicianship, as is the contrastingly rhythmic delivery of 1940s influences such as Anjos do Inferno and Os Cariocas.

It is incorrect to explain away the sensibilities of “in” and “out” of time as the legacy of, say, Angolan (drumming) and Italian (Bel Canto) traditions respectively. Freely floating melodies over a stable groove exist in several Latin American musical cultures that have their origins in West and Central Africa. For example, Candomblé music developed among Afro-Brazilian communities (the Yoruba, Fon and Bantu) amid the Atlantic slave trade of the 16th to 19th centuries, coalescing primarily in Bahia. Alongside other ceremonial traditions such as Afro-Cuban Batá, this music is characterised by a lead singer who creates tension by pulling around the melody, only to be resolved by the coro (choir) entering in time. This is a trick that João pulls off in the song Farolito: his phrasing in the verse is so tense, so consistently out, yet the chorus arrives right on the money, in its most relaxed and natural position. João is the quintessential Zen master at interlacing these two things, often creating balance by starting a phrase in time and ending it out, or vice versa. This is his true virtuosity, subtle and unmatched. Tom Jobim hit the nail on its head: João “was pulling the guitar in one way and singing the other way, which created a third thing that was profound.”

The most precious jewel in João’s crown is his manipulation of phrasing. It has been described as singing behind and before the beat, but it is way, way (WAY) more than that. In slow songs, João usually glides freely, placing his melodic phrases wherever he chooses, even in positions that no longer line up logically with the chords. Why we accept this violation of synchronisation is a subtlety of João’s artistry: the harmony is intact, the melody is intact, they don’t line up, but nevertheless everything is cool. A tremendous tension is generated, one which speaks to the omnipotence of the phrase. An example of Tempo Rubato I particularly love is “Besame Mucho”, from a duo concert with Caetano Veloso in Buenos Aires, 2002. After Caetano sings this jaded bolero in his simple, gorgeous way, João takes over (at minute 4’12) with a miracle of phrasing, weaved delicately into the fabric of his gentle groove, devastatingly moving in its transformation of such a world-weary song. Gazing at his mentor in adoration and wonder, Caetano’s reactions are breathtakingly revealing.

As a test to his students, Gustav Leonhardt would cover over three lines of a random passage of any J.S. Bach score with a sheet of paper, asking them to deduce what was beneath. They could never guess: Bach’s music is highly unpredictable and the same is true of João’s phrasing. I challenge anybody to sing along to a tune and accurately predict the timing of his delivery. In this sense, João was a true improviser, in the same league as Lester Young and Lee Konitz, two saxophone players who had a similar ability to define themselves by self-imposing limitations. Although João liked to improvise harmonically, he was always selecting chord voicings from a discreet and finite repository of possibilities. In duo contexts João also loved to improvise accompanimental vocal counter melodies, often based on guide tones (notes which explicitly delineate the harmony). But way beyond this, João’s real depth in improvisation was expressed through his relentless exploration of phrasing. I cannot think of anyone who went deeper.

So whereas at slow tempos João’s secret weapon is Tempo Rubato, at faster, more rhythmic speeds a mischievous wizardry comes to light. His fixation with displacement, with moving entire phrases back or forwards by half or even a whole beat, can be heard in “Acontece Que Eu Sou Baiano” (as well as in the aforementioned “Garota de Ipanema“). But in “Pra Que Discutir Com Madame” João takes the idea of displacement to the extreme, an exceedingly difficult skill to conjure. For example, at minute 0’38 he shifts the phrase “Vamos acabar com o samba” backwards by a whole beat (actually forwards in time), starting it on beat four rather than on beat one, its natural position. The effect is a kind of discombobulation. Or how about the phrase “É música barata sem nenhum valor”, which is placed in three different positions: at minute 0’23 (4th division of beat 3), minute 1’46 (2nd division of beat 3) and minute 3’10 (2nd division of beat 4). This effect can of course be felt without knowing anything about divisions and beats.

These rhythmic magic tricks are accepted by the listener thanks to the intact preservation of the phrase and, well, the ineffable charm of João Gilberto, whose first ever band were called Enamorados do Ritmo (Rhythm Lovers). Alongside Caetano Veloso, João’s most important disciple was Gilberto Gil: “since I heard João for the first time, I have been striving to play like him, but perfection is a goal defended by the goalkeeper”. Dedicated “Para João, a música, a poesia e o amor”, Gil’s album “Gilbertos Samba” is an affectionate tribute that emulates and even extends the rhythmic implications of his mentor’s art.

The totality of what I’ve described above reveals the dual polyphony of João’s music: a polyrhythmic matrix generated by the coexistence of three independent layers (surdo, partido alto, rhythmic melody); and a three-part harmonic counterpoint emerging from the accumulation of bass-line, chord and voice.

Pronunciation and Sound

João accent reflects where he was born: Juazeiro da Bahia, in the northeastern musical hotbed of Brazil. Videos of live concerts make plain much he cares about the musical sound of words. Contorting his mouth into the strangest shapes in order to manipulate the colour of a vowel or the texture of a consonant, João treats each syllable as a microcosm of sonic possibilities. As a consequence, his pronunciation is eccentric. Vowels like “i”, for example in the word “Bahia”, are exaggerated, transformed into a nasal “ü”. The “de” of a word like “saudade” is often magnified too, coaxed into a squishy, throbbing texture. João’s use of elision to cut syllables and mutate the ends of words is radical, engendering an even more personalised delivery. He was, to put it mildly, fussy about these things, insisting during a recording session of “Rosa Morena” on 28 takes to get the pronunciation of the “o” just right. An example of João’s microscopic attention to detail: at minute 1’57 of the beautiful song “Curare”, his fuzzy consonants imitate the sound of a pandeiro with the words “tudo tudinho”. But not only that, they’re executed with the wonky swing so characteristic of music from Brazil. The deeper we listen, the more is disclosed.

With his song “Pra Ninguém”, Caetano Veloso immortalised João’s relationship to silence. “When I sing, I think of a clear, open space, and I’m going to play sound in it,” João said in 1968. “It is as if I’m writing on a blank piece of paper. It has to be very quiet for me to produce the sounds I’m thinking of. If there are other sounds around, the notes I want won’t have the same vibrations.” He seemed infatuated with the playfulness and onomatopoeia of pure sound, demonstrated by songs he wrote such as “Undiú” and “O Sapo”. The myth of João the youthful stoner practising relentlessly in a reverberant bathroom rings true. Blank paper, silence, toilets: these are the liminal spaces into which he unfolded his artistry. Paralysed by stage-fright and hypersensitive to acoustics his whole life (to the point of causing real trouble), I wonder if deep down João would have preferred to stay cooped up in his echoey banheiro than have to cope with the messiness of the real world. Irregardless, if cultivating and caring for the sound of music is our goal, we must accept him as our teacher.

The Rejection of Sentimentality

Compare João’s version of “Bahia con H” to the great Francisco Alves’. João’s mature musical proposition speaks to a deliberate wish to de-sentimentalise his repertoire. Dripping with romantic slides and vibrato, these gorgeous 1952 recordings betray the affectations idiomatic to so much of the 1940s and ‘50s North American singing that João heard on the radio growing up. But soon enough he purged them from his musical identity. Just six years later, his hit “Chega de Saudade” was released and the difference could not be starker: the portamento and vibrato are gone, the tone is brighter and the delivery is way more rhythmic. It’s almost as if a different person is singing. Put off by the old-fashioned style of the previous generation, the new wave of 1960s Brazilian musicians adopted this cooler delivery as a badge of honour.

In songs like “Retrato Em Branco e Preto” and “Rosa Morena”, João’s guitar underscores this de-sentimentalisation by altering or doubling the harmonic rhythm of a song – the speed at which the chords move. This rupture of the song’s formal structure is yet another technique with which João gently breaks apart the squareness of his repertoire, defying our expectations of symmetry. Occasionally (and revealingly), João adds a beat to a given bar, changing a 2/4 song momentarily to 3/4 in order to accommodate an elongated turn of phrase. These improvised transgressions of the harmonic rhythm and time signature – unthinkable in straight-ahead jazz – have parallels in the blues and in folk music from all over the world. Unconstrained by abstract notions of meter, singers have often maintained their structures supple enough to allow the delivery of text to remain free.

Take a beautifully sentimental song like “Eu Sei Que Vou Te Amar”, originally recorded by Maysa in 1959. João’s version is very different. At minute 0’26, for example, he doubles the harmonic rhythm, moving faster through the song and temporarily transforming 2/2 to 3/4. He also refuses to repeat the words “eu vou te amar” after each line, as in the original. Add to this a subtle reharmonisation and the song comes out a lot leaner. His speed is faster too. In fact, João often speeds up slow tunes and slows down fast ones. But he never chooses extreme tempos. At the same time, because of his ninja phrasing, his music often creates the illusion of sounding slower than it actually is – yet another sleight of hand. We’ve seen the things with which João was willing to take liberties when interpreting someone else’s song: the speed, meter, groove, key, harmony, harmonic rhythm, repetition of lyrics, pronunciation and phrasing. However, apart from a tiny handful of improvised exceptions, João never changed the melody. Don’t fuck with the melody!

And so…

We have so much to learn from him: about self-imposing restrictions on our art forms, about creating upper and lower limits, about making clear-minded stylistic decisions, about creating enclosed systems within which freedom nevertheless flourishes, about the inexhaustible elasticity of phrasing, about the relaxation of grooves, about the boundaries of interpretation, about deep listening, about minutiae and extremes, about simultaneity, about process and its relationship to content, about humility, restraint, minimalism and obsession.

One of João’s nicknames was O Zen-Baiano. It was my unfulfilled dream to hear him live. Had I been so fortunate, I’d have joined Caetano in affirming that “Gilberto was the greatest artist my soul ever encountered.” Just maybe, in my fantastical pantheon of imaginary music Gods, João Gilberto Prado Pereira de Oliveira, sat between Bach and Billie Holiday, is singing “Chega de Saudade” in an infinitely shifting loop, to a lucky crowd.

Click here for a playlist of all the João Gilberto songs linked in this article.

Read Fred Thomas’ ‘On João Gilberto’ interview for London Jazz News:

Fred Thomas on João Gilberto