Jamie Doe and Fred Thomas have been making music together since they were 11 years old.

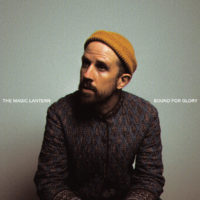

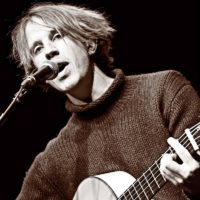

The Magic Lantern is the musical moniker of British Australian singer-songwriter and composer Jamie Doe, an artist dedicated to examining the limitless depth of human experience in our search for meaning.

To Everything A Season is his unashamedly emotional fifth album written in the months following his daughters birth and his fathers death six weeks later. Describing their brief meeting in a dementia nursing home Jamie says:

“In that cathartic moment I saw myself in my father, and my daughter in me and I felt joy and grief in overlapping waves, beautiful and complicated, which continue to ripple outward. These songs are my attempt to make sense of this incredible time where both ends of the circle of life touched.”

To Everything A Season crackles with the quiet intensity of a family’s rawest and most intimate moments. Recorded live over over four days at the legendary La Buissonne studio in France by Gérard de Haro, the sound of To Everything A Season captures a vivid emotional immediacy, the richness of the ensemble arrangements and spirited improvisation belying the devastating songwriting. Working with a septet drawn from London’s thriving jazz scene To Everything A Season is both dreamy and direct, making use of the space around Jamie’s arresting voice to emphasis it’s emotional weight.

Lyrically, To Everything A Season is The Magic Lantern’s most powerful and accomplished achievement, a mature work that establishes Doe as one of the most confident lyricists writing today. With themes of loops and cycles threaded through the album, the lyric draws on references as diverse as the Bible, the records of John Coltrane and the helix structure of DNA.

Born in Australia, before moving to the UK at 12, Jamie adopted the stage name of The Magic Lanternand began writing songs while studying philosophy in Bristol. He lives in London and has released four full length albums and two EPs in addition to a compilation of other artists versions of his songs for the male suicide prevention charity CALM. He has toured the UK, Europe and Australia with acts as diverse as folk singer This is The Kit, Sam Lee, and Alabaster Deplume. He is a Professor at the Guildhall School of Music & Drama and teaches on the songwriting faculty at the Institute for Contemporary Music Performance.

The Magic Lantern has received praise from numerous publications including The Guardian, Songlines, Acoustic Magazine and Folk Radio UK as well as BBC Radio 1’s Huw Stephens, BBC 6 Music’s Lauren Laverne, Guy Garvey, Tom Robinson, BBC Radio 3’s Late Junction , Night Tracks and BBC Radio 2’s Jamie Cullum, Mark Radcliffe and Bob Harris among others.

To Everything A Season is out via Hectic Eclectic / La Buissonne Records

“Extraordinary. Beautiful poised singing, amazing lyrics and hypnotic production” Tom Robinson, BBC Radio 6 Music

“Gorgeous, beautiful. This stopped me in my tracks. Slightly surreal, in all the right ways” Jamie Cullum, BBC Radio 2

“Dreamy, beautiful. Something very, very special” Lauren Laverne, BBC6 Music

“Bitter sweet, beautiful music” Verity Sharp, BBC Radio 3 Late Juntion

“A classic album. I love it!” Bob Harris, BBC Radio 2

“Pretty special i think you’ll agree” Tom Robinson, BBC 6 Music

“Warmly recommended, especially to anyone who thinks meaningful eccentricity and sheer originality are rare commodities in contemporary music” Chris Parker, The Vortex

“Quirky and charming” Timeout

“The Magic Lantern fuse delicate folk flickerings with the depth a richness of a jazz timbre. Their sounds combine to provide a refreshingly deep and mysterious atmosphere, full of imagery….extremely accessible, but in no way due to the following of common formulae” Pejhy

“The Magic Lantern’s set was a heightened sensory experience that contained all of the dramatics of a piece of theatre. There is a certain Jeff Buckley quality to the arrangements and diction, a songwriting capacity that, like Joanna Newsom’s, is utterly otherworldly and densely descriptive….a symphonic fuzziness to the band’s sound in which the instrumentation intermingles to create an overwhelming experience” Folk Radio Live Review

“They’re making bold, heartwrenching (and still bloody clever) songs” Neu Magazine

“9/10 – Something quite special, The Magic Lantern have produced a remarkable, enchanting and genuinely affecting album that’s sure to bring them the attention they deserve” Planetnotion.com

“An 11-Track Stunner. There’s no real way of putting this in a subtle manner, so it’s better to be blunt and open about it from the off – ‘A World in a Grain of Sand’ is a must-buy” Clixie.co.uk

“**** Beautiful, engrossing music” musicOMH.com

“4.5/5 – Wonderfully composed” Sound Revolution.com