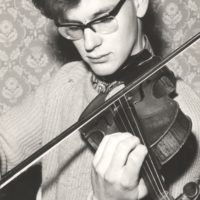

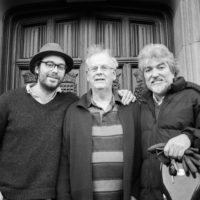

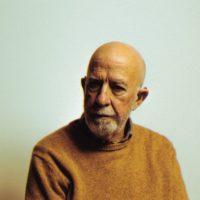

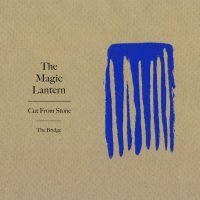

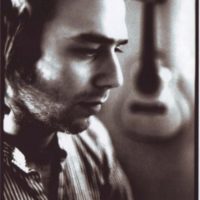

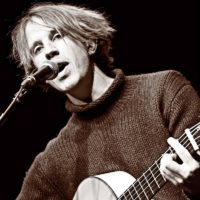

Peter Thomas and Fred Thomas released their father-son “Duo” record in 2015, to celebrate Peter’s 70th birthday.

Fred Thomas – piano

Engineered, Mixed & Mastered by Alex Bonney

Produced by Fred Thomas

Design by Nuria Torres

Dedicated to the memory of Tony Fisher, Alice Corser & David CorserReleased by F-IRE Label, January 9, 2015

Dedicated to the memory of Tony Fisher, Alice Corser & David Corser

Buy the album here.

Some thoughts on the music and why we chose it

Felix Mendelssohn’s music somehow feels like part of my blood and tissue; there’s a powerful (but sleepy) imprint on my memory of being gently woken on countless mornings by his soaring melodies and naive figurations floating from my Dad’s violin up into my bedroom and inhabiting my half-asleep mind. The Piano Trio Opus 49 included in our program holds a nostalgic place in my heart. I played the cello part when I was 16 and it’s no exaggeration to admit that this experience of duetting in lush counterpoint with the violin was transformative. Mendelssohn’s subtle piano writing style was greatly influenced by Robert Schumann, whose songs Peter grew to love when he was a teenager. I’m sure they helped him cultivate his singing style. But perhaps Schumann influenced my dad in more ways than one: the composer lamented, “You have no idea how often I practically throw money out of the window.”

Despite Peter’s childhood fondness for Schumann, Schumann himself believed Franz Schubert should be “the favourite of youth. He gives what youth desires – an overflowing heart, daring thoughts, and speedy deeds.” Brahms, who insisted that “there is no song of Schubert’s from which one cannot learn something”, may not have approved of choosing just two Schubert songs from his six hundred-plus collection. One easy choice, however, was An Sylvia, which Peter often heard his own father Stanley play by ear on the piano.

When Ludwig van Beethoven died, a distraught Schubert was present as torch-bearer. A year later, on his own death-bed aged just thirty-one, Schubert asked to be buried next to his idol. Both Schubert and Beethoven have been Peter’s staple diet for most of seventy years; his beloved ‘Spring’ Sonata Opus 24, dedicated to Count von Fries, appears here in all its battered glory. And although it’s a tricky piece, it seems Beethoven couldn’t have cared less, inquiring “do you believe that I think of a wretched fiddle when the spirit speaks to me?”

Ironically and perhaps hypocritically, the Musical Courier wrote in 1899 of Richard Strauss, “the man who wrote this outrageously hideous noise no longer deserving of the word music, is either lunatic, or he is rapidly approaching idiocy.” Current opinion is a little kinder; a besotted and proselytizing Glenn Gould did his bit by proclaiming Strauss a greater text-setter than Schubert. Of all his own output, Strauss rated his songs the highest, and they’re not bad for a man who considered himself a “first-class second-rate composer”.

When I asked what he misses about playing in orchestras, Peter promptly replied, “nothing.” Followed sheepishly by, “except Mahler.” I’m not sure what I can add about the song Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen. It’s too big and too profound. Gustav Mahler passed on a deep sense of spiritualised landscape and the transformation of nature to his musical godchild, Anton von Webern. Some years ago, following in the footsteps of Webern and his own son Peter, my Dad and I made a musical pilgrimage to the Austrian Alps – a kind of lads on tour for aspiring muso-walkers. Between schnitzels we listened to Webern’s complete works. This didn’t take long. Captivated by tiny alpine flowers, Webern was a master of miniature; Mahler, by contrast, dealt in the monumental. “If you think you’re boring your audience, go slower not faster”, he said, advice we’ve followed in the making of this record.

If the prospect of listening to all this music resembles an exhausting schlepp up Mount Schwarzenbergspitzen or a headphone-assisted guided tour of the Habsburg Empire, fear not, help is at hand. Alfred Schnittke’s Pantomime and Igor Stravinsky’s Valse pour les Enfants (“my music is best understood by children and animals”) inject a shot of Slavic irony and Orlando Gibbons’ Fantasia à 2 offers perhaps the most exquisitely balanced exposition of equal two-part writing I can think of: disarmingly simple yet aurally beguiling – a distillation of what it means for two voices to sing together. Then, if you can feel Morton Feldman blow a whispered draft of cold, cleansing New York air though this sticky swamp of Austro-German mush, so much the better. His was a search for music that “just cleans everything away” – breathe deep, there’s more swamp to come.

A word on the order of program. It’s devised not only to juxtapose pieces in flattering ways, but also to suggest links between composers: Webern adored Schubert and orchestrated several of his songs in his youth; Mendelssohn was largely responsible for the mainstream popularisation of Bach in the nineteenth century; Schnittke may well have been thinking of the Alberti bass-lines of Mozart and Beethoven when composing his roguish Suite in the Old Style; and Stravinsky wanted to banish the operas of Strauss to “whichever purgatory punishes triumphant banality” – the temptation to pair them together was just too delicious to resist.

Morton Feldman once mused, “for years I said if I could only find a comfortable chair I would rival Mozart”. It’s a common complaint that Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart remains the most interpretatively challenging composer of all, easy to listen to but uniquely difficult to actualise. Interpreters may spend a lifetime searching for the perfect proportions, the appropriate intensity and pitch, and all this within an extremely focussed sphere of expression – a kind of musical Goldilocks Zone where only Mozart lives. His Sonata No. 12 in G Major, K27 was written when he was eleven years old.

And finally, Johann Sebastian Bach, the old master. My first inkling of his importance was when, aged ten, I was unsuccessfully bribed by Peter to learn his 371 harmonised chorales (my favourite of which concludes this program). Later, upon receiving CDs of Bach’s complete keyboard music from my uncle Ezekiel, I was hooked, in the same way Peter was as a teenager studying with Eli Goren. For so many people Bach’s music means the cosmos. It’s the most transcendent and all-encompassing thing we know. Significantly, all the composers mentioned above seem to have felt the same. Mendelssohn: “The greatest music in the world.” Schumann: “Studying Bach convinces us that we are all numbskulls.” Schubert: “Bach has done everything completely.” Beethoven: “Not brook but sea should be his name.” Mahler: “In Bach the vital cells of music are united as the world is in God.” Webern: “Bach composed everything.” Mozart: “Now there is music from which a man can learn something.” And Wagner, whose work it pains me (and relieves many) to exclude: “The most stupendous miracle in all music!”

What’s the relevant common thread linking all these Bach-worshipping composers? For our purposes, it’s their profound significance to us somewhere along the way and the continuity of musical love handed down through a generation. Mendelssohn believed – and I suspect my Dad does too – that music “fills the soul with a thousand things better than words.” In celebration of Peter’s monumental accomplishment of lingering on for seventy years, of everything he has taught me, of the diversity of music and of generous friends’ charitable giving, we hope you will consign these words, in the spirit of old age, to mental oblivion, and take simple pleasure in the sounds within.